|

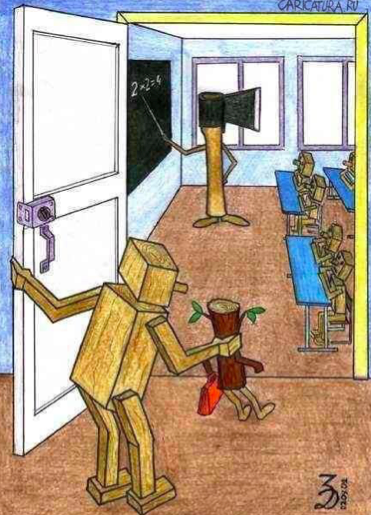

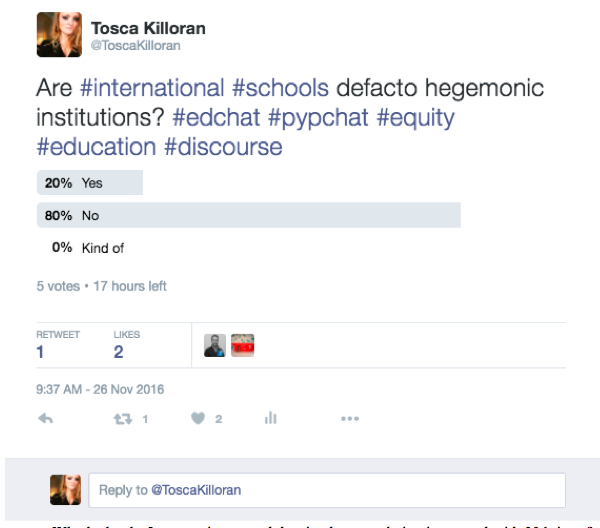

For a long time I read articles about American education and thought, thank Buddha I don’t live there, thank Zeus I work in international education. Our students and teachers come from diverse backgrounds; we have inclusive schools that espouse missions, visions and values grounded in equity discourse. We have a focus on mother tongue, we support enrichment and learning needs. We have no issues of equity. We have it made. I would look at images such as the meme below and steam (3D, 2001). We don’t want to chop young minds into replicas of our own thinking! We espouse personalized and individualized learning, character education, and global citizenship. Indeed, for a long time I dismissed the issues of equity within American schools as distinctly an American problem. As a Canadian, I framed the struggles in the USA within the context of slavery, and gun ownership, and the seemingly inherent violence of the American mindset. Even as a well-travelled, self-proclaimed global nomad, I couched all my American friends who lived away from the USA as free from oppression, and those who chose to stay as part of the system. How lucky, thought I, to have none of the problems in international education that are within American public schools. And then, I looked again. There has always been something lurking in the subconscious of most international teachers; together on a Friday night talk will turn to questions deep within the shadows of our minds. We question, are we teaching the 1% to just become more of the 1%? How equitable is it to force our way of learning on all these diverse children- demanding they espouse the inherently western values of our system? How many other narratives do we actually infuse within our practice? How equitable is our enclave of ridiculously priced education to the host nations we squat within? How equitable are we to the local staff that landscape, take our trash away, or clean our rooms? How equitable are we to the local co-teachers who earn a fraction of the wage of their international counterparts? Sure, they earn a better wage than they would get “outside” but this parsimonious justification seems wrong at heart. We look to Kant’s notion that there is an equality of men grounded in a moral context (Mills, 1997, p. 16), but often within international schools we see this egalitarianism as only possessed by the fiscally mobile. Within the walls of international schools we seek to create “deliberate diversity” (IB World Magazine, 2014, p. 27), but our piece meal attempts at equity seem only to reframe the cultural patterns we have created and the accepted norms of how international education has always been. In the light of day, I decided to poll my network of 6,489 connections on social media and was left with many more questions than answers. Why had only 5 connections voted despite the tweet being interacted with 396 times? Who was it that voted yes, educators, parents, or non-educators? It was messy data that begged for answers I couldn’t get. Evans (2013) notes “taking charge of an equity agenda is more than ideological discourse and slogans” found within our mission, visions and values (p. 461). It is grounded in “talking out loud about issues” (p. 463) and focusing a beam of light into shadows. I suppose that beam of light for me starts with the silencing of my own voice. In listening to the community outside the walls of our school, or of those inside our school rendered silent by language, or socio-economic, or cultural barriers. Perhaps I can illuminate and make meaning of their stories (Guajardo et al., 2016, p. 27). Establishing relationships of trust through conversations give individual’s narratives power. They provide opportunities for schools to reframe truths, assumptions, and challenges instead as areas of ambiguity, spaces for reflection, and chances for innovation (Eubanks et al., 1997). Literally, inviting the stranger that works with us into a dialogue could be the key to better equity. “[Richard Nisbett] uses conversations to shape a scientific inquiry, to help him link up questions so they have a narrative form. He starts in on a problem by trying to see how it works in real life. He interviews people. He surveys people over the phone. He snoops in archival records. He reads broadly. He triangulates on an understanding” (Steele, 2010, p. 21). It is our job as leaders to triangulate on understanding by seeking and using the stories in our communities (Rigby & Treadway, 2015, p. 332). We need to shift to artists that speak with many tongues, with multiple sensibilities (Smith, 2009, p. 373). Through those voices we will become sharp instruments of transformation but rather than whittling down the true nature of our communities, we will turn that ax against the systems of hegemony that expect us to do just that. References

Ax 3D. (2001). Using image reverse generator of TinEye this image was first trawled 02. 29.08 however the image itself is dated 2001. The image source is a mystery, and out of 16.6 billion images searched has 221matches on the Internet, which makes it a fantastic meme. Eubanks, E., Parish, R., & Smith, D. (1997). Changing the discourse in schools. In Hall, P.M, ed., Race, ethnicity and multiculturalism policy and practice. New York: Garland Publishing, pp. 151-167. Evans, A., E. (2013). Educational leaders as policy actors and equity advocates. In Tillman, L. & Scheurich, J.J., Eds., Handbook of research on educational leadership and equity and diversity. New York: Routledge, pp. 459-475. Guajardo, M., A., Guajardo, F., Janson, C., & Militello, M. (2016). Reframing community partnerships in education: uniting the power of place and wisdom of people. New York, NY: Routlage, Taylor & Francis Group, p. 27. Mills, C. (1997). The Racial Contract. Cornell University Press, Cornell University., p. 16 Newbery, C., Ed. (2014). The continuing quest for inclusion. IB World: The magazine of the International Baccalaureate. September Issue 70, pp. 24-28. Rigby, J.G. & Tredway, L. (2015). Actions matter: How school leaders enact equity principles. In Khalifa, M., Arnold, N.W., Osanloo, A, & Grant, C. M., Handbook on urban educational leadership. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 329-346. Smith, Z., (2009). Speaking in Tongues, from New York Review of Books Feb 26, In Samet, E., D. (2015). Leadership: Essential writings by our greatest thinkers. New York NY: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., p. 373. Steele, C., M. (2010). Whistling Vivaldi: and other clues to how stereotypes affect us. New York NY: W.W. Norton & Company, p. 21.

1 Comment

3/4/2024 04:41:47 pm

nice blog<a href="https://edissy.com/tosca-online-training">Tosca Online Training</a>

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Author:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed